I hate yard signs. I dislike them almost as much as I loathe those inflatable, blowie-uppy-thingys that people put in their yards for Halloween and Christmas.

My Midwestern upbringing suggests a tendency towards simplicity. Nice clean lines, everything in its place, and no clutter. Signs in my yard advertising my feelings about holidays or politicians, um no. Well, except for this year. This year I actually have not one, but three yard signs, and one bumper sticker letting my neighbors and passersby know who I support in this election year.

I put my first yard sign up at the end of last spring to let my State Representative Norine Hammond know how I felt about the current fiscal situation at the institution where I work – Western Illinois University. After a year in which WIU and other universities in the state of Illinois received no funding, I felt like my interests and concerns were not being heard. I sent letter after letter to Representative Hammond, signed postcards expressing my unease, attended rallies, and still I felt like I was being ignored. So I put out a yard sign that asked Representative Hammond to do her job and fully fund WIU.

What I had hoped for was a conversation with Representative Hammond, an opportunity where she could present her argument and we could respectfully exchange ideas about how to work our way out of the fiscal quagmire we find ourselves in. As a public servant, the quality of my work-life depends in large part on sound judgement and collaborative decision making. The extent to which citizens like you and I are involved in the decision making process signals how democratic a system is. The degree to which those choices are sound, goes a long way in determining how effective citizens in a democracy will be in solving its problems. And none of this can take place without an open conversation.

And while I have seen plenty of State Representative Hammond in my mailbox and on TV, I have yet to have a conversation with her. And neither has her opponent, John Curtis.

Public debates are a fundamental part of the political process. The point of a debate is to be able to hear how the candidates stand on certain positions. And yet time and time again Representative Hammond has declined the opportunity to debate John Curtis.

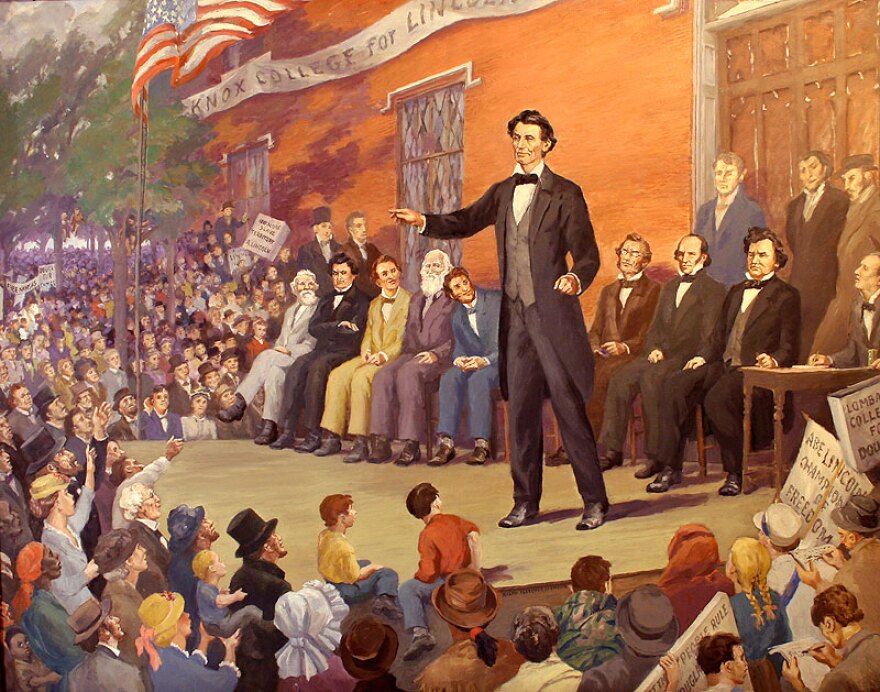

The idea of public officials trading arguments and counterarguments before citizens is not new. In fact, in the United States the political debate goes back to the Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, when Abraham Lincoln challenged Sen. Stephen Douglas to a series of face-to-face, three-hour debates in seven different towns across Illinois. Lincoln and Douglas effectively went out “on tour,” discussing their differing views on slavery and the laws and practices regarding it with the voters they were competing to represent.

It troubles me that Representative Hammond seems not to be the least bit interested in engaging her opponent. Nor does she seem to be interested in allowing her those she currently represents to ask her difficult questions. Her refusal to debate has made it clear to me that she is unwilling to participate in the most fundamental parts of the democratic process.

Larry Sabato, a professor of Political Science at the University of Virginia writes, “Every election is determined by the people who show up.” I have already exercised my right to vote. Voting, like debating, is a civil sacrament. Go exercise that civil sacrament and vote.

Heather McIlvaine-Newsad is a Professor of Anthropology at Western Illinois University.

The opinions expressed are not necessarily those of the University or Tri States Public Radio. Diverse viewpoints are welcome and encouraged.